'Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo' at the MET in NYC explores the intercultural exchange between Tavernier (1844-1889) and the Indigenous Pomo community of Elem

By Medicine Man Gallery on

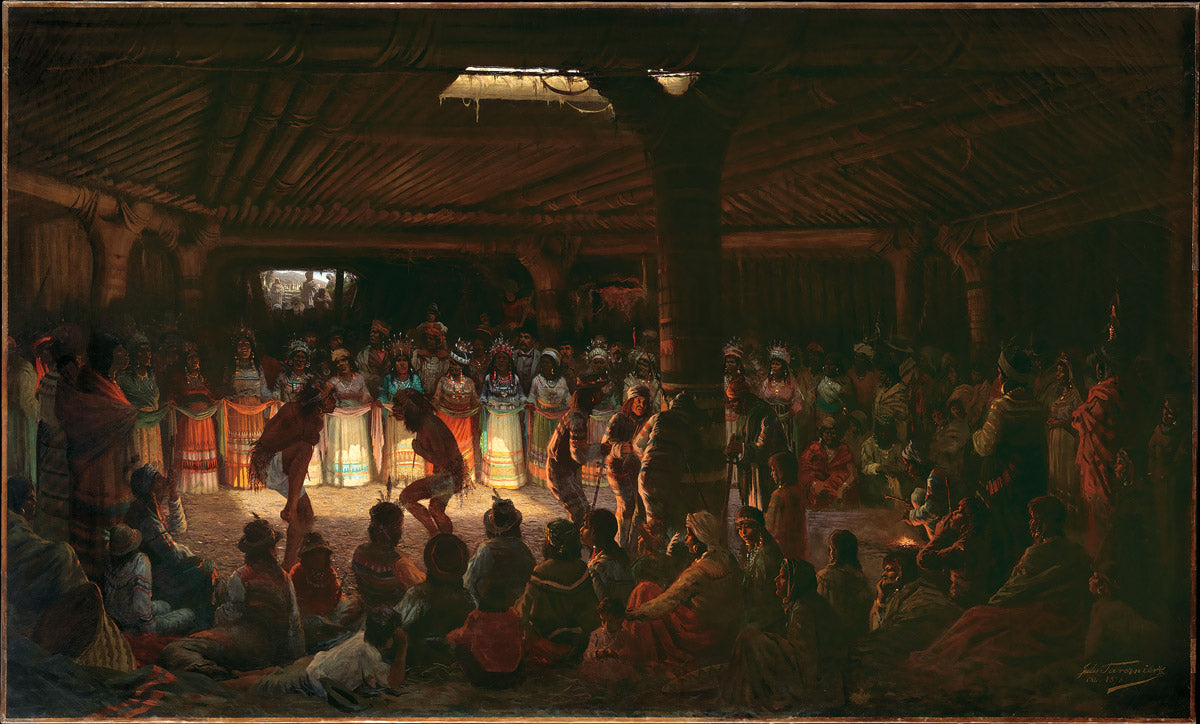

Jules Tavernier, Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California, 1878. Oil on canvas, 48 × 72 1/4 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired through the Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2016.

When thinking of the best places to see Western art in America, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York doesn’t typically jump to mind. It should. As with every other collecting area featured at the Met, its selection is exemplary. Nocturnes by Fredric Remington highlight the collection in my opinion.

Another Western painting from the Met’s collection which has always fascinated me receives the spotlight this fall: Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California (1878) by Jules Tavernier. The oil on canvas painting measures 48 × 72 1/4 inches and on my visits has always appeared in the same gallery with Emanuel Leutze’s famed Washington Crossing the Delaware. Through November 28, however, the painting serves as centerpiece for an exhibition entitled, “Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo,” which explores the intercultural exchange between French-born and -trained American artist Jules Tavernier (1844–1889) and the Indigenous Pomo community of Elem at Clear Lake in Northern California.

Through exquisite detail, a subtle use of brilliant color and one of the most compelling examples of the depiction of light in any painting I’ve ever laid eyes on, Tavernier takes onlookers into the Elm Pomo roundhouse where we see a ceremonial dance (mfom Xe, or “people dance,”) taking place with a crowd of onlookers surrounding it. Tavernier did have permission from the tribe to witness the scene.

I have been mesmerized by the painting on numerous visits. Dominated in its gallery by the Washington picture and largely unheralded, the painting never receives much of a crowd allowing for extended close inspection.

It’s a spectacular example of what I like to call a “take you there” painting as the artist does more than merely depict the scene, he transports you there. You hear the music. Feel the foot stomps of the dancers. The dust gets on your clothes.

Tavernier spent two years working on this masterpiece, filling his composition with nearly one hundred figures including Pomo dancers, musicians and artists, as well as non-Native on-lookers including San Francisco’s leading banker at the time, Tiburcio Parrott, who commissioned the painting. Parrott was then operating a toxic mercury mine on the community’s ancestral homelands which was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1990 and continues harming the sovereign people of the present-day Elem Indian Colony.

The exhibition further features approximately 60 works by a range of artists—paintings, prints, watercolors, and photographs—telling the story of Tavernier’s travels through Nebraska, Wyoming, California and the Hawaiian Islands. Feathered “art baskets” by the Pomo on display are exceptionally beautiful. The tribes micro-mini baskets are astonishing.

Fortunately, the of voices and perspectives of Pomo cultural leaders and curators are included in the exhibition, offering new interpretations on the subject. Major paintings by Tavernier are shown alongside examples of 19th- to 21st-century Pomo basketry and regalia, including works by weaver Clint McKay (Dry Creek Pomo/Wappo/Wintun, born 1965), celebrating the resiliency of Indigenous Pomo peoples and highlighting their continued cultural presence today.

To learn more about Tavernier’s Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California and the Pomo people today, watch the below video produced in conjunction with the exhibition by the Met.