Kim Wiggins' western vision stands out at Briscoe Museum in San Antonio

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Once you see a Kim Wiggins (b. 1959/1960; Roswell, N.M.) painting, you’ll never mistake one for anyone else. Their radiating lines and near iridescent colors recall tropical bird wings. His pictures tell Western stories in a relatable, representational, graphic style.

Four Wiggins paintings on view at the Briscoe Western Art Museum highlighted my March 2023 visit to San Antonio; I will focus on three of them.

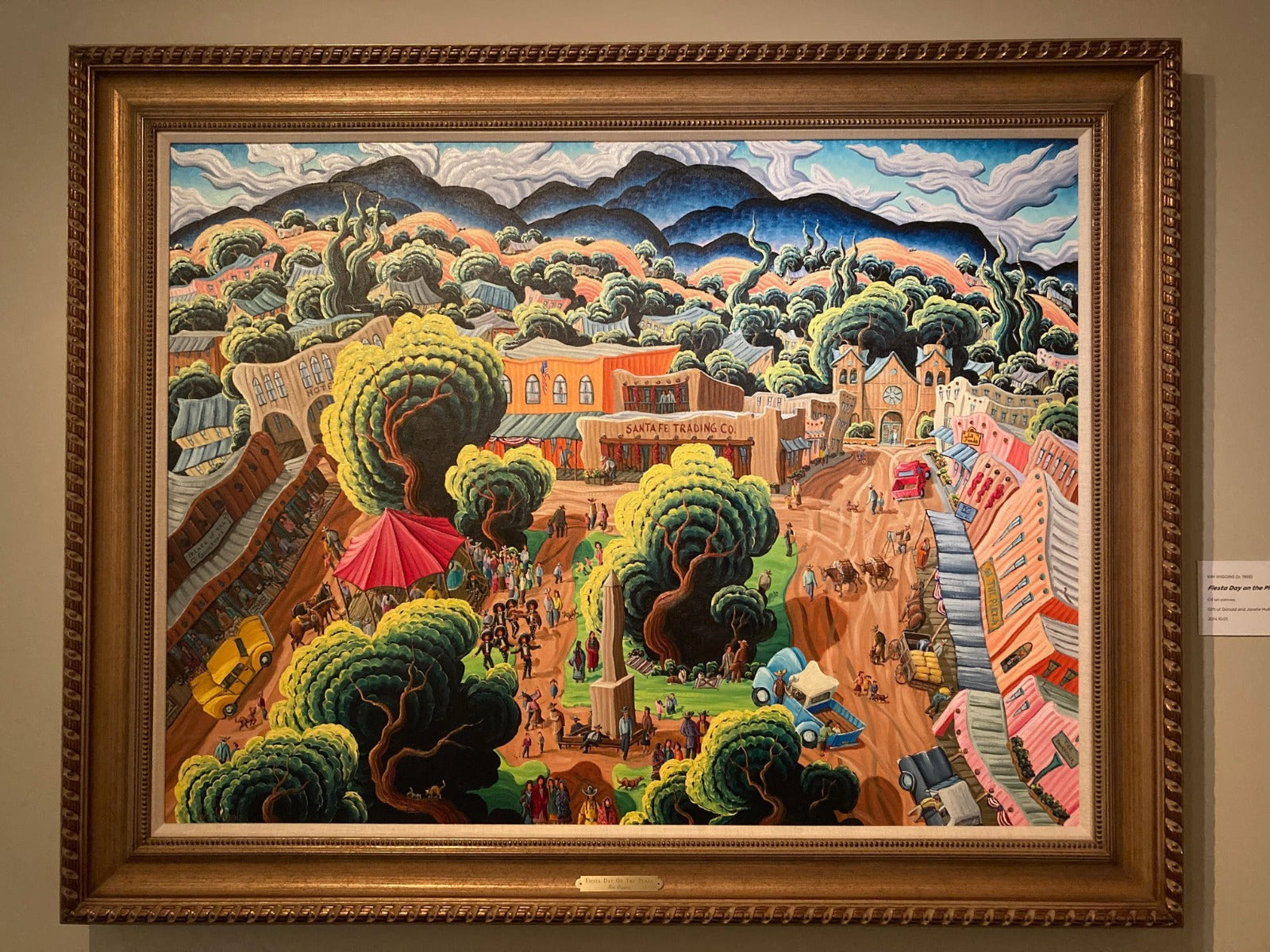

Kim Wiggins, Fiesta Day on the Plaza, 2003. Oil on canvas. Briscoe Museum of Western Art

Fiesta Day on the Plaza (2003)

Wiggins’ vision of a bustling Santa Fe Plaza circa the 1950s or ‘60s judging from the cars dazzles with brilliantly contrasting yellow and greens in the foreground tree canopies.

He populates the picture with a wonderful assortment of people. A Mariachi band. Native artists selling their work under the overhang at the Palace of Governors just like today. Folks gathered around a red canopied stage watching dancing – in the exact same spot you’ll find them doing so in 2023.

A painter works at his easel by the red pickup parked outside the La Fonda Hotel.

While much of Santa Fe’s Plaza remains the same today, much has obviously changed. The streets are paved, for one. The La Fonda and Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi are familiar, but the Santa Fe Trading Co. has been replaced by Malouf on the Plaza and other retailers.

A more frequent and longtime visitor to Santa Fe than myself will surely find countless other references still remaining or long removed.

The prominent obelisk, a monument to Union Civil War soldiers commending their bravery for fighting “savage Indians,” was torn down by activists on Indigenous People’s Day in 2020. As recently as two week’s week prior to this article’s publication in March of 2023, heated public debate surrounded what to do with the monument site.

Joining the people are dogs, cats (find them on the tree branches along the painting’s lower edge), burros carrying loads and horses pulling carts and supporting riders.

Consciously or subconsciously, the wobbly “fun house mirrors” effect recalls Chaim Soutine with the bendy evergreen trees a nod to van Gogh’s cypresses in The Starry Night.

Kim Wiggins, Last Tally at Bosque Grande, 1867 - Goodnight-Loving Trail Series, detail, 2021. Oil on Canvas. Briscoe Western Art Museum

Last Tally at Bosque Grande, 1867 – Goodnight/Loving Trail Series (2021)

Acquired as the museum purchase during the Briscoe’s annual Night of Artists fundraising event in 2022, this painting’s purple clouds leap off the walls. Depicted is a herd of famous cattleman John Chisum’s (not to be confused with Jesse Chisholm, another Texas rancher, of Chisholm Trail fame) longhorns crossing the Pecos River on their way to the Bosque Redondo Diné (Navajo) concentration camp in the eastern part of what is now New Mexico.

Shame on the Briscoe Museum for the gallery label terming Bosque Redondo an “Indian Reservation.”

Forced out of their ancestral homelands at gunpoint in 1864 by the federal government, some 10,000 Diné were inhumanly marched on foot (the Long Walk) across what is now New Mexico. Hundreds died along the way. Transplanted to marginal lands and forced to rely on meager federal subsistence for food, Bosque Redondo is a horror story of American history, not a “reservation.”

Words matter and this beautiful painting has a gruesome backstory.

Depicted on horseback in the crimson shirt is Chisum, counting heads. The cattle are on their way to Bosque Redondo to provide beef for the soldiers and Diné living there.

By the time the Diné negotiated a return to their homelands and what could more appropriately be called a “reservation” in 1868, “2,000 internees, one out of four, (had) died of dysentery, exposure, or starvation, and are buried in unmarked graves.”

The colors are immaculate.

Notice the detailing in the clouds, again reminiscent of those bird feathers.

![]()

Kim Wiggins, Frank Chisum - Wild West Icon, detail, 2020. Oil on canvas. Briscoe Museum of Western Art

Frank Chisum – Wild West Icon (2020)

Unusual for Wiggins, this painting takes on a portrait – up and down – format. The action cuts diagonally across the middle of the picture.

How’s this for resonance: John Chisum, from the above painting, purchased the formerly enslaved Frank Chisum, who only later chose that surname, for $400 in 1860. John eventually freed Frank, who’s shown here.

When recalling the West purely with fondness and romance, these are the ugly details and stories important not to overlook – and one million more like them persisting to the present day.

Frank Chisum would go on to participate in the Lincoln County War of Billy the Kid fame, and Wiggins is referenced by “Cowboys & Indians” magazine as believing the Danny Glover Joshua Deets character in Larry McMurtry’s “Lonesome Dove” novel was based on him.

Amazing.

Dramatic storytelling in this picture as Chisum leads a horse heard up a dangerous mountain pass. Chisum’s mount precariously balances on the side of the cliff, one airborne leg off of it. A wild stallion – lasso around its neck – struggles against Chisum whose resolute countenance utterly contrasts the panic in the eyes of his horse. A tad overly wrought with human exceptionalism, but this specific scene is a fiction.

Wiggins comes by his Texas and New Mexico ranching paintings honestly. He was raised on a ranch in southern New Mexico and still lives in state. He joined Medicine Man Gallery Owner Mark Sublette for a particularly enjoyable episode of Sublette’s “Art Dealer Diaries” podcast.