Mateo Romero 'American Landscapes' at Medicine Man Gallery

By Medicine Man Gallery on

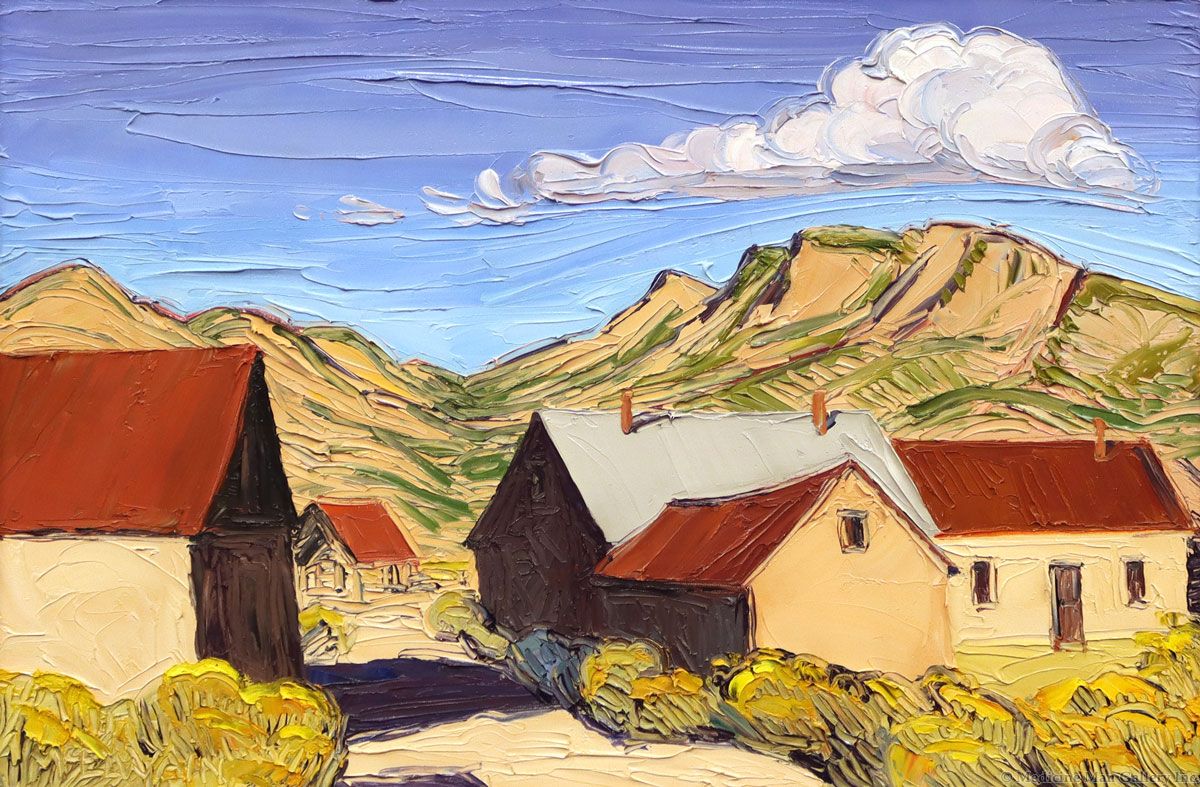

Mateo Romero - Tsi Ping Owingeh #10, Oil, 48" x 60", c. 2022

Mateo Romero makes clear he is a Native American painter. He also makes clear that the direction his career has taken him increasingly distances his work from that genre.

“I'm an American painter,” Romero said. “I am Cochiti Pueblo, I'm an enrolled tribal member, but the work is not self-consciously Native. It's not didactically Native. You don't have to know that I'm from Cochiti Pueblo to look at the paintings and to connect with the paintings and appreciate what the paintings are about. They are American landscapes.”

Those American landscapes are the focus of a solo show at Medicine Man Gallery this August.

While surely influenced by Native American art – his father was a Dorothy Dunn School painter, his older brother Diego a massively influential potter who was roommates at the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe with the massively influential Tony Abeyta – talk to Mateo Romero about his work and he’ll lead you down a fascinating path of art history across the West, the nation and the world.

Nathan Olivera and Bay Area Figurative painters like Richard Diebenkorn and David Parks. Victor Higgins, Wayne Thiebaud, Willem de Kooning, Cézanne. These are the forebearers of Romero’s now distinctive lusciously impastoed and vibrantly colored northern New Mexico landscapes.

“The vocabulary of this muscular painting, that's Wayne Thiebaud with those delicatessen pieces with this huge quarter inch paint of sardines and half inch ice creams. That, to me, is the beginning of this very muscular, physical, turgid paint surface,” Romero explains. “It's very sensual; because it's Wane Thiebaud it's very well done. Nathan Olivera is the corollary to me with the brushwork. The physical surface is not as hugely active, but it has this sweeping motion, the gesture.”

Sweeping motion. Gesture. Physical painting. Heavy paint buildup. Active surfaces. Northern New Mexico landscapes. Those characteristics all point in one specific direction.

Louisa McElwain - Rancho Viejo II, Oil on Canvas, 24" x 36", c. 1989

Louisa McElwain

“Louisa McElwain is the direct progenitor of this style of palette knife oil paintings of northern New Mexico landscape, and even more specific than northern New Mexico, it's Ghost Ranch, it’s Abiquiu, it's Rio Chama, it's Chimayo, it’s Cuyamungue. It's where I live in Pojoaque,” Romero acknowledged. “There are many people doing this now – there's probably a half dozen artists doing this style, I'm one of them – and the artists that are more honest (admit) everyone's looked at her work, everyone's borrowed directly from her work; some of the artists doing it now will not admit that, they pretend like they just came up with this stuff on their own. That's bullshit. You guys directly lifted this from what she was doing, as did I.”

Romero met McElwain a number of times when he was working at the Pojoaque Cultural Center where she would apply for permits to paint there. He never went out painting with her, however, a story he candidly details in his appearance on the Medicine Man Gallery “Art Dealer Diaries” podcast.

“To say something like I’m painting with a palette knife and oil paint and I'm doing El Pedernal or I'm doing Rio Chama and to not say that Louisa McElwain was here before me and that I looked at her work and that I knew her, that would be disingenuous,” Romero said. “That would be me being insecure about my work in relation to hers.”

Forget the artist, that one comment from Romero says all anyone needs to know about the person he is. Refreshing talk in an art world still too often promoting the myth of unique, unaffiliated, artistic genius – lightning bolts of creativity from the sky owing to nothing previous – let alone an art world just now becoming comfortable with crediting women artists for their work.

Despite the influence, Romero has established his own distinct voice working in this style. His paintings incorporate more reds and yellows and oranges than McElwain, who owned and explored every shade of blue. Where McElwain tended to focus on sky and clouds with low horizon lines, Mateo Romero is of the earth, more often focusing on the soil and vegetation with higher horizon lines. For all their similarities, after having seen only a few paintings by each artist, 100 out of 100 times an onlooker would be able to identify who did which in a side-by-side comparison.

Frybread

With an Indigenous father and white mother, growing up in Berkeley, CA while now living in the Pueblo of Pojoaque, attending college in the Ivy League at Dartmouth and spending a year in postgraduate work at IAIA, Romero’s unique background gives him unique opinions. The confidence he’s acquired over a much-lauded career – he and his brother shared the 2019 Native Treasures Living Treasures Award – emboldens him to share those opinions.

His thoughts on currents in contemporary Native American art are eye-opening to say the least.

“Museum curators have very specific agendas. There's an agenda on the side of these curators to have work which is very self-consciously Native. It's very didactic. They want written words now, you have to have text,” Romero observes. “It's what white curators cull out of Native communities that titillates white audiences at the Whitney or The Met. It's not intrinsically Native curation, its colonial curation.”

Romero decries how the Native American art often favored in the mainstream has come to rely on gags, tropes about “powwow vans” and banged up cars.

“You have to have frybread written in your painting; isn’t there a lot of frybread? Isn’t that the punchline of every joke? Some kind of smoke signals moment where (Native people) look at each other and say, ‘frybread,’ and start laughing,” Romero said. “It's got to have that hook for these people to think that it's important or that it resonates.”

Without dismissing his Native heritage, Romero comes at his artwork from a distinctly painterly, art historical background unlike many contemporary Native painters who use the medium primarily to express their Indigeneity and perspectives on Native life and issues. While his work clearly descends from Fritz Scholder, T.C. Cannon, Earl Biss and the greats of Native American art, it equally descends from J.M.W. Turner, Monet, Van Gogh, the Hudson River School, the Taos Society and the greats of landscape painting.

“I had earlier series of work which had more ideas about Native (culture) embedded in there, more Native subject matter,” Romero said. “What I'm doing now is American painting. It's as American a painting as is a Victor Higgins or a Louisa McElwain. It's not specifically a Native at all. Anywhere that people appreciate landscape painting, (my work) will resonate.”