BYU Museum of Art opening historic exhibition of Maynard Dixon paintings

By Medicine Man Gallery on

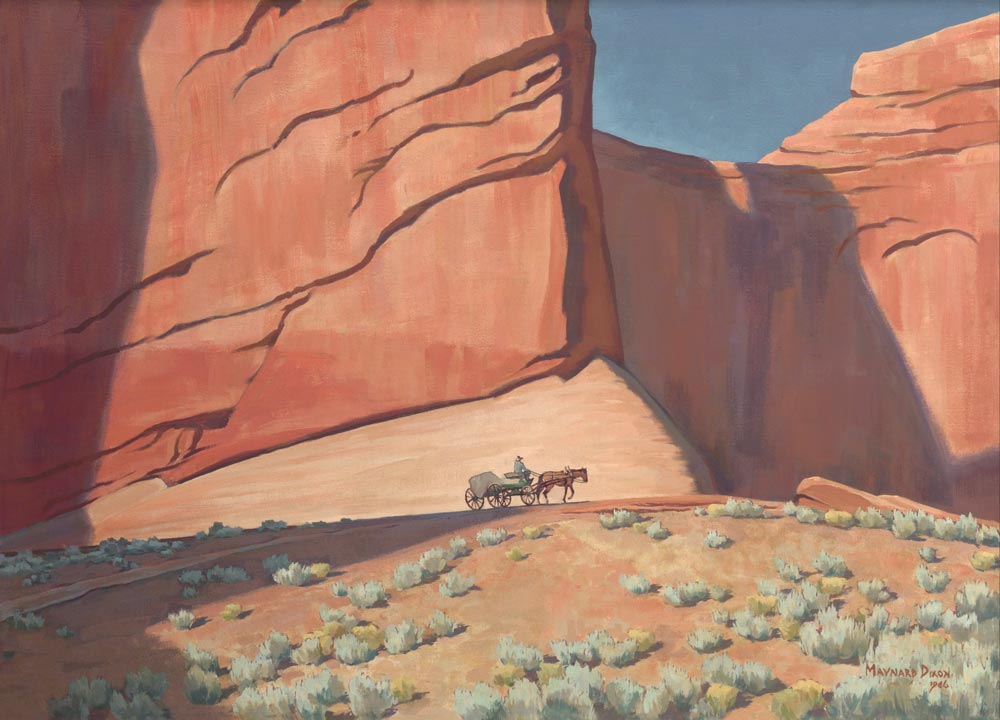

Maynard Dixon, A Lonesome Journey, 1946 | Photo Courtesy BYU Museum of Art

Violence defined the West of Fredric Remington and Charlie Russell. Gunfights. Animal slaughters. Stolen land.

Cowboys shooting Indians. Cowboys shooting each other. Cowboys killing wildlife.

All of what they painted and sculpted happened, of course, but their artwork goes beyond simple observation. Their artwork mostly glorified this barbarism.

Russell and Remington were Manifest Destiney artists, romanticizing white settler colonialism’s take-by-force and divine right approach to the West. Whoever was abused or robbed or died along the way, well… all in the name of “progress.”

Not so with Maynard Dixon. A turn of the century contemporary of Russell and Remington, Dixon’s West offered empathy. Dixon painted a quieter West. A more peaceful West.

If a historic Western artist exists to represent the kinder nature of humanity, surely it is Dixon, not Russell or Remington. The Brigham Young University Museum of Art highlights Dixon’s West in an upcoming exhibition, “Maynard Dixon: Searching for Home,” presenting stark contrasts between his subject matter and that of Russell and Remington, while noting moral contradictions within his own work.

“I do largely see Dixon very sympathetically… more sensitive in his treatment of Western peoples particularly,” exhibition curator and Curator of American Art at BYU Kenneth Hartvigsen said. “He's fascinated by the Native Americans who lived here. He's fascinated by Mexican Americans that he meets. He's fascinated by the Mormon farmers he meets in southern Utah. He really falls in love with anyone who was able to do, I think, what he ultimately wanted to do, which was to become a permanent resident of this space.”

While Dixon was a Westerner, living in San Francisco, what he aspired to be was a Southwesterner. He viewed the two very differently. Of the Southwesterners he admired, he did more than meet them, he came to know them, understand them, live with them for periods.

“There's a wonderful story where during the Depression he was on this trip in Taos and was talking with some of the elders of the community about his financial difficulties and his concerns,” Hartvigsen said. “One of the men in the village said, ‘I have this plot of land, you can come and live with us if you need to.’ I think that closeness he felt with those people reveals his love, his true love for these people.”

BYU Museum of Art Exterior| Photo Courtesy BYU Museum of Art

Dixon and his wife, famed photographer Dorthea Lange, were down and out during the Great Depression. Bad. Kindness the likes of which he experienced while staying at Taos Pueblo could understandably be interpreted as the basis for the tenderness in his paintings. A tenderness absent from Remington and existing to a far lesser degree with Russell.

Here, however, is where contradictions in Dixon’s work appear. “Searching for Home” exhibits examples of Dixon’s social realism paintings, underrecognized paintings which may be a revelation to even fans of Dixon. Depicted are fellow sufferers of the Depression in California. Striking dock workers. People he referred to as “the forgotten men.”

At this same time, Lange was photographing the Depression and migrant camps in California. The couple divorced in 1935 and Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” the most famous photographic portrait in American history, was taken in 1936.

Dixon understood hardship. He understood hunger. He understood a deck stacked against you.

None of this understanding, however, made its way into his paintings of Native people.

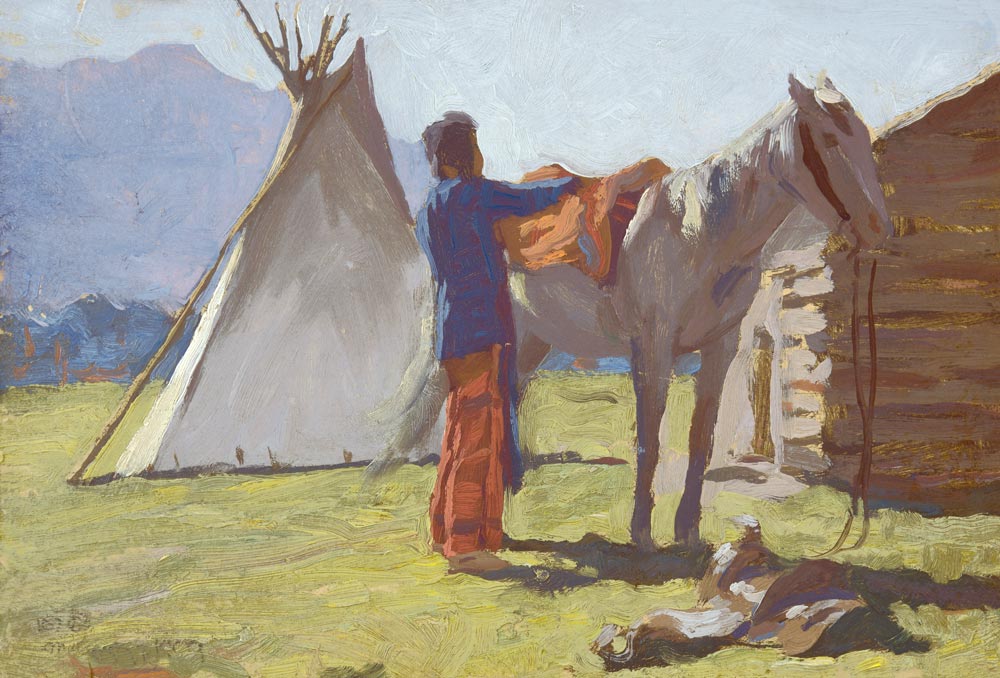

“Where I see the complications in Dixon's depiction of Native Americans especially is only in that they do still feel a little bit timeless to me,” Hartvigsen explained. “He starts painting a lot of Native American subjects in about 1914, 1915. If you look at that time period in Native American and American relations, that's a time when people were being sent to the boarding schools and where a lot of Native ceremonies are being outlawed, or at least very strictly controlled by government entities. He doesn't give us any sense of that and I think that kind of timelessness can be a way of allowing people to enjoy the West without seeing some of those complicated realities.”

The social consciousness evident in his social realism paintings of struggling whites in California didn’t make its way into his paintings of struggling Indians in the Southwest, although surely he would have recognized it.

“It's completely appropriate to hold both of these things as true: Dixon loved the Native American peoples that he knew and interacted with, and that he was, with his art, doing his very best to show their life and to celebrate their life, but also from a 21st century perspective, to look back and say sometimes (he) fell short of depicting some of the realities that would be more helpful in providing a space for these people to move forward in American society,” Hartvigsen said. “(Dixon) does talk to people about (allowing) his imagination to move freely. He does occasionally say things like, ‘I wouldn't expect somebody to come to the Southwest and see what I painted.’ He is acknowledging that there is a process of creation here and he asserts a certain authorship, a certain position of authority in saying, ‘I have the right to paint these Native ceremonies or Native peoples in a certain way, even if it's not strictly true.’ That's where things get a little bit gray for me because on one hand, I say art doesn't have to be always fully documentary, it doesn't have to be always representational. An artist should have a right to paint what they want, the way they want, to some extent, but there is sometimes an assertion of his authorship of these people that comes across as a problematic from a 21st century perspective.”

The BYU Museum of Art possesses the largest museum collection of Dixon paintings. “Searching for Home” (October 28, 2002 – September 23, 2023) will be the first time in over 20 years where a majority of the collection will be shown together in a single exhibition.

Maynard Dixon, Flathead Indian and Pony, 1909 | Photo Courtesy BYU Museum of Art