Sasquatch as You've Never Seen Him Before

By Chadd Scott on

The silhouette of a supposed Bigfoot captured in the famed 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film showing a large, hairy, long-striding, bipedal, ape-like creature striding across a dry riverbed in northern California has become ubiquitous across America. While never officially debunked, the recording is almost surely a scam and popular recreations of Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, descended from the film have turned the legend into a cryptozoological Santa Claus.

Over the past 30 years, the Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot silhouette has shown up on t-shirts, bumper stickers, key chains, beer cans, lawn ornaments and every other imaginable tchotchke for sale along roadsides from coast-to-coast. It has launched a cottage industry of Bigfoot “chasers” on TV and social media.

“Bring-your-own” Bigfoot sticker car bumper installation outside 'Sensing Sasquatch' exhibition at High Desert Museum in Bend, OR. Photo by Todd Cary.

Sasquatch isn’t a joke to everyone, however, and a group of Native American artists from the Pacific Northwest have been brought together by the High Desert Museum in Bend, OR – Sasquatch country – to share legends and likenesses of the animal through their artwork. Phillip Cash Cash, (Nez Perce, Cayuse), HollyAnna CougarTracks DeCoteau Littlebull (Yakama, Nez Perce, Cayuse, Cree), Charlene “Tillie” Moody (Warm Springs), Frank Buffalo Hyde (Nez Perce, Onondaga) and Rocky LaRock (Salish) explore Sasquatch’s past, present and future in the High Desert region through an Indigenous lens.

“It became clear right from the beginning when we started talking to the artists we were interested in and our Indigenous advisor on the project (Cash Cash), (the) amount of reverence and respect that Native people across North America and in the High Desert region have for Sasquatch,” Hayley Brazier, Donald M. Kerr Curator of Natural History at the High Desert Museum, said. “That meant the tone of the exhibit needed to be completely different than you might suspect with that more typical pop culture Bigfoot image.”

Native peoples of the Plateau have long known about, encountered, depicted, and told stories of Sasquatch.

“You do see Sasquatch in the exhibit represented by the artists in various ways, but the High Desert Museum – the staff, the curators – we never inserted that image in the exhibit ourselves,” Brazier said. “We were careful to take a step back and let the artists’ work speak for itself.”

Visitor to 'Sensing Sasquatch' exhibition admiring Phillip Cash Cash, Nez Perce, Cayuse, 'Bigfoot Rattle.' Photo by Bill Jorgens.-1

High Desert Sasquatch

The original word for Sasquatch is “Sasq’ets,” which comes from the Halq’emeylem language of Coast Salish First Nation peoples from southwestern British Columbia. Sasquatch’s habitat is often associated with the wet rainforests of the coastal Pacific Northwest, but Sasquatch also lives beyond the green, lush climate. In the High Desert region, Sasquatch strides among the dry canyonlands, ponderosa pine forests, and shrublands.

Exhibition visitors are introduced to the Indigenous Plateau of the High Desert where Native peoples have long come into contact with and exchanged stories about Sasquatch. A digital language map shows the various names for Sasquatch across the Indigenous Plateau and beyond. On view are representations, stories, and artwork about the creature and examples of how those vary between tribes and across regions.

Outside the exhibition, a “bring-your-own” sticker interactive encourages visitors to reflect on the popularity and kitsch of mainstream Sasquatch representations. Guests can place stickers on the back of a Subaru that’s driving away into the distance – symbolically transporting away their Sasquatch stereotypes and entering a new realm of experience and insight.

“It's not to say that (pop culture) image of Bigfoot or Sasquatch is bad, it's just different,” Brazier said. “This might be how you recognize Sasquatch, that’s ok, put a sticker on the car, this car is going to drive off into that wet rainforest and then we're going to ask you to enter the exhibit and have a different experience, one that's High Desert related, one that looks at Sasquatch from a totally different lens.”

Sasquatch as a conscious being with the agency to communicate with humans in direct opposition to the popular view of Sasquatch as shy and running away and hiding when humans approach. Sasquatch as a protective entity. Sasquatch as an elder, a relative, and a spiritual guide who appears to deliver important messages to humans.

Sasquatch encounters as a blessing, not something to be feared.

Or chased.

'Sensing Sasquatch' exhibition installation view at High Desert Museum in Bend, OR. Photo by BIll Jorgens.

To be or not to be, that is NOT the Question!

Bigfoot “hunters” touting their cryptozoological – the study of mythological or extinct animals – credentials trekking off into the bush trying to find evidence of its existence are on the opposite end of the Sasquatch spectrum from the artists with work on view at the High Desert Museum.

“All the artworks have a strong reverence and respect for Sasquatch, and Sasquatch, seen from their perspective, is not an entity that you go seek out or ‘hunt,’” Brazier explained. “If you have an encounter, that's a powerful experience, but it's not something you're meant to track. There's a lot more agency that Sasquatch has in this artwork, he chooses – or she chooses, depending on the artist which pronouns they use for Sasquatch – but (Sasquatch) choose to communicate with humans. Sasquatch has more flexibility and movement and power in these environments than they're often given credit for.”

Sasquatch as spiritual, not marketable.

Unlike the chasers, the creature’s existence isn’t considered in the exhibition.

“Not to negate those worlds and that research and what people do, but for all the Native partners we spoke to, the topic isn't up for debate,” Brazier said. “It's not a question, and it would have been totally wrong or even inappropriate to bring that question up in the exhibit because it's not what Indigenous people often question, it’s just truth. Does he or does he not exist, taking that out leaves more room to go into what are Native perspective on Sasquatch, it opens up more space for that kind of learning and takes that question mark totally out of the equation.”

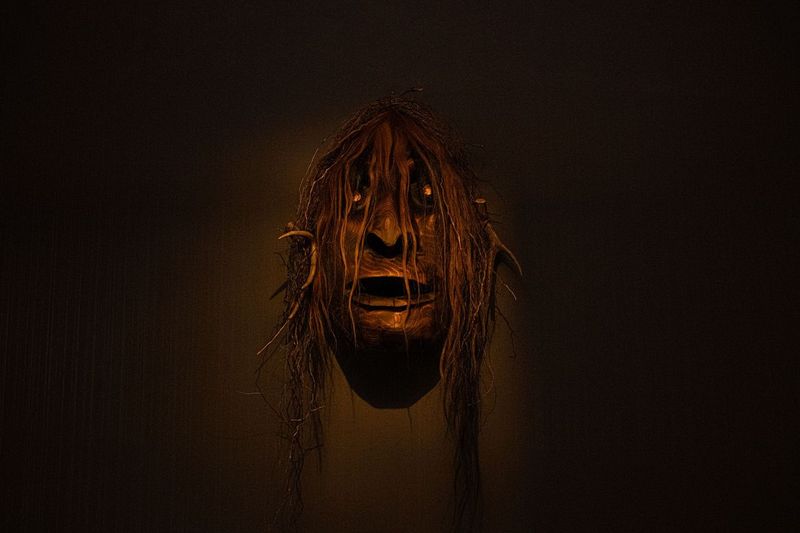

Rocky LaRock, Salish, carved Sasquatch mask. Photo by Bill Jorgens.

Sasquatch Artwork

Sasquatch has appeared in Indigenous artworks and stories for thousands of years and this continues today. Buffalo Hyde’s commissioned large-scale futuristic Sasquatch painting with 3-D relief elements illustrates the perception of Sasquatch as an interdimensional enigma who lurked in the forest for millennia to a modern being that continues living among humans.

Littlebull’s commissioned “Protector” sculpture depicts Sasquatch as a protective “big sister,” not a predator, but one who deserves respect and safeguarding. CougarTracks is an avid hunter and gatherer. She grew up on the Yakama Indian Reservation in southern Washington state and considers herself “a protector of KwiKwiyai, or Bigfoot. Bigfoot is considered the protector of all living things.”

When she finds signs of Sasquatch activity, she makes sure to obscure it, preventing “chasers” from harassing the creature.

For the exhibition, Cash Cash created a 13-foot-tall “Bigfoot Rattle,” made of cottonwood, that Sasquatch would use. A contemporary carved mask by LaRock shows visitors that knowledge of Sasquatch is both ancient and contemporary.

Sasquatch as you’ve never seen him – or her.

“Sensing Sasquatch” will be on view through January 12, 2025.