Remnants of the Past - Francis Livingston's Urban and Southwestern Scenes

Remnants of the Past

Francis Livingston’s urban and southwestern scenes hold open a door to an era that has passed

by Gussie Fauntleroy

Published online courtesy of Southwest Art, January 2002

Francis Livingston, Dual Wheels, oil, 14"x22"

It was a bit of a blow, finding out he didn’t have what it takes to be a comic-book artist. There he was, young Francis Livingston, in his first year at the Rocky Mountain School of Art in Denver. All through boyhood e’d collected comic books and copied – with good likeness, he thought – the drawings of super-heroes, western heroes, and even animal characters. At his Edmond, OK, high school he’d been singled out by an art teacher as “most artistic.” And even though regular kid stuff like fishing and playing tennis occupied his time as much as drawing, Livingston knew he had some talent. His parents supported his interest in art school, and finally, there he was, enrolled in a course being taught by an artist well known in the comic-book world.

But Livingston remembers the instructor telling him, “You’re not good at the sequential stuff.” He could draw a character just fine the first time, but in the next sequence, the same character in a different pose with a different expression needs to look like the same character. Livingston’s didn’t – they came out different each time.

That appraisal cast a pall on Livingston’s goal of becoming a comic book artist. But his instructor asked to see some of his other drawings and paintings. He nodded with approval at the talent he saw in them and suggested that Livingston sign up for courses in fine art.

Today, more than a quarter of a century later, the artist still loves comic-book art and takes his son to a major comic-book convention in San Diego, CA, each year. But he is more than happy with his own path, divergent though it has been from his original plan. Studies at the San Francisco Academy of Art, 10 years of teaching there, and many years of illustration work have led to his present successful career in fine-art painting and representation in galleries across the country.

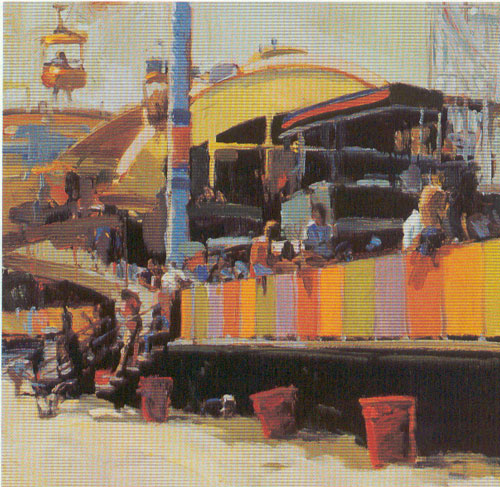

Francis Livingston, Late Summer Boardwalk, oil, 15"x15"

Livingston now lives near Sun Valley, ID, with his wife, artist Sue Rother, and their two sons. Inspired by N.C. Wyeth’s studio in Chadds Ford, PA, Livinston built his own work space to have enormous windows that flood the high-ceilinged room with cool, consistent north light. Outside, a cloak of cottonwoods and aspens lies between the studio and the Big Wood River, home to river otter and trout. Eagles and osprey soar above the trees, and for the past several summers a mother moose and her calves have munched their way across the property. In the valley’s clear light and mountain-bordered beauty, Livingston is just a little bit removed from the high-tech frequency of modern life.

The artists’ paintings, as well, invite the viewer to step away from the urgent pace of contemporary life. Although some of his work involves urban imagery, the scenes are quiet, often almost devoid of people. Carnivals and boardwalks seem nearly deserted. Theaters and other buildings are shut down and gently decrepit, their architectural grandeur faded but still visible. In a style that suggests rather than illustrates, Livingston’s paintings hold open a door to earlier times.

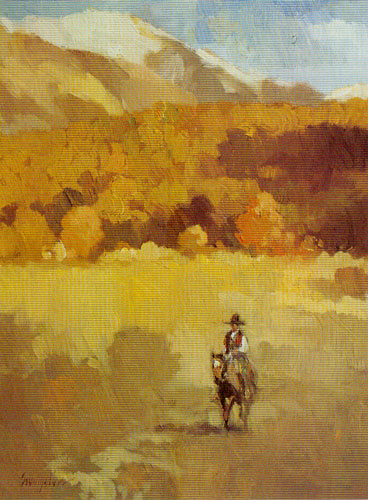

Similarly, his southwestern imagery offers immense, open landscapes and Indian pueblo scenes as they could have existed a century or more ago. As with the urban imagery, there are few historical details in these paintings that would pin them to a specific point in time. Yet they, too, speak of an era that has passed.

Francis Livingston, Lone Rider, oil, 12"x9"

“I think I have an affinity for scenes from the past. I always go back to certain periods that had, for example, better fashion, better cars, when everything was wonderfully designed and crafted,” he reflects. “If I paint an old Ferris wheel with a few little figures to denote scale, or if I paint an old adobe building or pueblo with a few figures in it, to me these are very compatible. Both draw on a sense of a different time, where you can lose yourself in what it might have been like back then.”

It comes as no surprise to learn that Livingston’s work has been influenced by painters John Sloan (1871-1951) and Edward Hopper (1882-1967). Like Livingston, they painted both urban and southwestern imagery. And both spent time in Taos, NM, a place to which Livingston has long been drawn. Among the first works of original art he experienced as a boy were paintings by the early 20th-century Taos artists at the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City, OK.

Even Livingston’s urban scenes pass through a filter of southwestern sensibility , as he gravitates to areas of saturated color, moments of clear light, strong shadows, contrasts, and pattern. “Cities are often hazy and gray, so urban imagery can tend to get grim. But I never liked painting grim things,” he says. “Even if I paint unkept, run-down buildings, I never want to make it downbeat.”

Livingston’s ability to find the visually compelling side of things is one he acquired through years of commercial illustration work, when he was asked to portray everything from the grand to the ordinary. “After a while you get the sense that anything can be worth painting and anything can be painted. Now I would feel confined if I painted only one kind of imagery,” he says.

“I look at a painting almost in an abstract way,” Livingston continues. “It can be a buffalo or a Ferris wheel or anything else, and I say to myself, ‘Here’s one shape and here’s another.’ In the original composition I think about the narrative a little, but mostly I ask how the painting can achieve…..