Fred Fellows: Home on the Range

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Western Art Collector magazine, November 2007

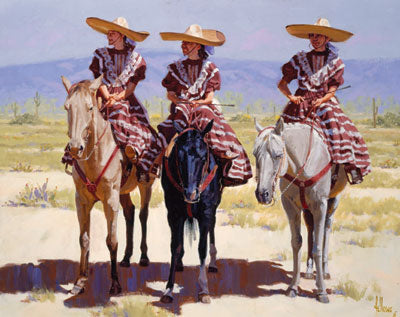

Fred Fellows is equally at home roping, throwing and branding, or creating respected art in his studio. But whichever he decides to do it is a given that he will do it well, because Fred Fellows is cowboy grit and dedicated artist personified.

Painter and sculptor Fred Fellows is a man who has always known what he wants. And what he wants is to be a cowboy and an artist. On those points he hasn’t wavered since he was old enough to shave.

“My grandparents lived in Oklahoma, and I grew up hearing stories of the West. Like a lot of little kids, I thought the West was about horses and cows. I wanted a horse.”

Fred and his favorite roping horse, Eagle, in front of his authentic style mesquite corral. The ranch’s windmill is visible in the background. Photography by Valerie Hayken Photography and Design.

Even after his step-father, mother, brother, and he moved to California in his formative years, Fred never let go of the dream to own a horse. While still in high school, he went to work repairing saddles after classes ended each day. Fellows figured he was on his way to fulfilling one of his dreams—to live the cowboy life.

As for the rest, Fellows says, “I had just graduated high school, wasn’t going to college or anything like that. I had no art experience, but I wanted to go to art school. My granddad was an engineer. He told me he’d send me to any engineering school in the world if you’ll be a civil engineer and take over this business eventually. I said ‘No thanks.’ I still wanted to go to art school. He told me I’d have to do it on my own. Adios. And that was it.”

So Fellows continued on the path he’d chosen.

“I worked for seven years repairing saddles and finally started to make new ones. Then I served my apprenticeship making new saddles. From there I bought a mare and started roping rodeos.

Fellows fell in love with the cowboy life, and it fell in love with him. When an opportunity arose to go north to Monolith, California to work on a ranch, he jumped at it. But being a cowboy was only part of Fred’s dream.

“I was working on this ranch and my step-dad showed up there one day and asked me if I wanted to go to work as an artist for Northrop. I went to Northrop and began drawing little schematics in their art department and after seven years I became art director.”

But that still didn’t satisfy Fred’s drive to be an artist.

“I just really wanted to paint, because it’s easy. So I moved to Taos, ran out of money and had to go back to work at North American Aviation.

“But, what I found out was that I wanted to live the life, too. Living it was as important as painting it was to me. I wanted to live in a place where I could ride horses. So I finally, I saved up enough and moved to Montana and just painted.”

Still, Fellows needed to make a living. So he came up with an ingenious way to turn his art and his passion for guns into a profit.

“Once a year in Kalispell, Montana they had an antique gun show. Antique gun collectors formed the Montana Antique Gun Collectors Association and once a year they’d have this gun show.

And then they’d have a gun show over in Spokane, Washington. And then they’d have a gun show in Salt Lake City, and they’d have a gun show in Denver. The biggest gun show was in Las Vegas.

“I found that I could take paintings and stand outside of a log cabin and put an $8 frame on them and I could trade a painting for a gun. Then I could go sell the gun. I knew what I was looking for. So I would go over to a guy and say, ‘What do you want for this old, rusty 1894 Colt Winchester?’

“The guy would say, ‘I want $150 bucks for it.’

“I’d say, ‘Would you trade that for that painting over there that I did?’

“The guy would say, ‘You know, I’ve never taken my wife anything. I’ll trade with you.’

“So I went and got the painting, and I’d hand it to him and he’d give me the gun and I’d shake his hand and I’d walk to another part of the gun show and I’d go up to a guy and say, ‘What will you give me for this gun?’

“He’d say, ‘I saw that gun over on that table there and he wants $150 for it and it’s not worth a dime over $100.’

“I’d say, ‘Would you give me $140?’

“He’d say, ‘Yeah, I’ll give you $140 for it.’

“And so essentially I sold my painting for $140. And then sometimes I’d take a gun home and I’d look it and fix it up—work on it. And I just loved them anyway. And so I built up a small collection of guns. Every once in a while I’d keep one. That’s how I managed to make a living for a while.

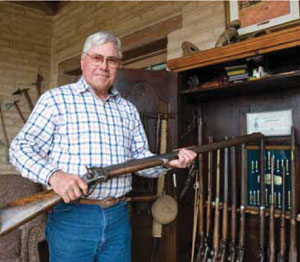

Also in the Fellows collection is a Springfield Carbine that was used at the Custer fight as part of the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Around the same time, Fellows got his first big break.

“Margaret Jamison, of Jamison Galleries in Santa Fe was the first gallery to have my work and she actually sold one of my paintings for $1,000, which I just couldn’t believe. That was more than I’d made in a year.”

Fred takes a back seat while his sculptor-wife Deborah Copenhaver Fellows, gets their favorite burro, Yum-Yum, to roll over.

Shortly thereafter and while he was still trading his paintings for guns, the Cowboy Artists of America (CAA), formed four years earlier, accepted Fellows as a member. The year was 1969.

“The whole thing started as a bunch of artists who would get together once a year and go on a ride. It was started as a camp out.

Fred is a consummate horseman.

“And then Joe Beeler (founding member of the CAA) and the director of the newly formed Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City decided they should get together and have an art show. At the time everybody was just selling art out of the back of their cars. So they started to have a show. Once the Cowboy Artists started showing, it changed everything.”

That was almost forty years ago, and Fellows has never looked back. Twice he has served as president of the CAA. His artistry has been celebrated throughout the world and his days of trading paintings for guns and barely scraping by are a thing of the distant past.

These days Fellows’ paintings and sculptures can be found in museum collections such as the Buffalo Bill Cody Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, and in private and corporate collections. His list of awards is impressive, and includes the Grumbacker Fine Art award and the Printing Institute of America award. He’s one of a very few artists who have won both gold and silver medals in both painting and sculpture at CAA shows. In fact, he’s won two gold and three silver medals and a Best of Show award.

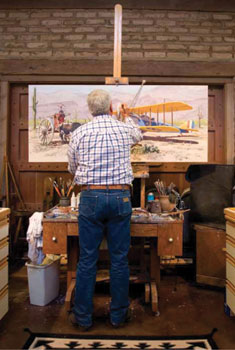

At the time of writing, Fred was busy on his work for the 2007 CAA show. He told us, ”a radical department in subject matter.”

I’ve always wanted to paint an airplane. I was the first one to paint a car or truck for the CAA Show. I believed it was the car or truck that changed the West. A cowboy would have to get up in the morning and ride all day to get to a little old shack on the other side of the ranch. He’d have to stay overnight, check the herd, the cattle, etc. When you have a truck, you could tow a trailer with the horse and have the same thing done in less than a day. If you were going to a rodeo, you had to ride your horse there, and have a tent. It was a rough deal. So the truck and car changed the West completely.” Fellows still lives the cowboy life in southern Arizona with his artist-wife Deborah. Their scenic, working ranch spread boasts horses, some steers, a burro, a dog, and assorted others, along with two studios. He and his wife continue to rope competitively, and they regularly help with roundups at nearby ranches. The Fellows’ front yard looks out on 74,000 acres that have been designated by Congress as a national conservation easement area and can never be developed. When it comes to living his dreams, Fred Fellows has exactly what he wants.

Fred handles one of the many classic rifles, pistols and buffalo guns he has collected over the years. Many of the guns have colorful history, including one specimen used at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Early in his career, Fred used to exchange paintings for guns, which he later traded for cash. Then he started to repair and eventually build his own collection.

Published online with permission of Western Art Collector magazine.