Glenn Dean: Honoring the Location

Glenn Dean: Honoring the Location

Californian Glenn Dean strives to be true to the time and place he is painting, and to synthesize his observations in much the way historical plein air painters once did in the West.

by M. Stephen Doherty

Published online courtesy PleinAir, July, 2014

It is hard to find words that adequately express the essential aspects of painting because that creative enterprise involves the deepest, most inexplicable, and sincerest emotions connected to visual images. Artists have a difficult time saying why they feel a certain way about a shape, color, texture, or space, but those feelings are among the most important elements of the painting process. No tube of paint, pattern of brushwork, or promotional strategy is as critical to the success of a painting as the connection between the artist’s head, hand, and heart. For more than a decade, Glenn Dean has been using that essential connection between his mind and body to create paintings that express his understanding of art as well as his emotional and intellectual response to the landscape.

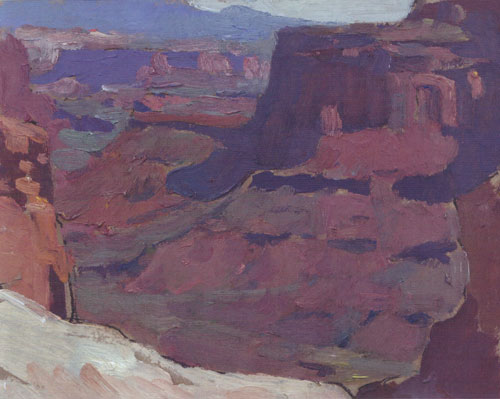

Glenn Dean, Canyonlands, 2013, oil, 6"x8"

Collection of the artist; Plein air

After years of being out in the field with his paints, he knows what speaks to him and how to share his perceptions with viewers of his paintings. Those perceptions come through with references to the historical California artists who influence him, most notably Maynard Dixon and Edgar Payne. “I’ve looked at paintings by a lot of the great Western painters, and invariably there is a strong design underlying the representations of the landscape,” Dean says. “The artists made a conscious effort to move the viewers’ eyes through the pictures while offering the painters natural response to things. Influenced by that work, I look for an integrated design of the shapes, colors, spaces, and patterns in the landscape. I think about ways to crop an image within the rectangular canvas. Finally, I try to put all of these pictorial elements down on canvas in a natural way that doesn’t seem forced."

When he is painting outdoors, Dean tries to “get at things,” meaning that he grabs the most critically important elements of the landscape and avoids becoming too literal or detailed with his paintings. “I ask myself, ‘How can I paint the big effect of what I am seeing without nitpicking or getting caught up in detail?”’ he explains. “How can I paint the essential light and dark relationships and create the suggestion of detail? Nature is too overwhelming, and there is a strict limit on the amount o f time I can be out there painting. Moreover, I am not really interested in representing things exactly as they appear. I consider my plein air sketches to be studies that may inform studio paintings created with more time for thought, evaluation, and refinement. I try to figure things out in those plein air sketches and then pursue the ideas inherent in the sketches once I am in the studio.”

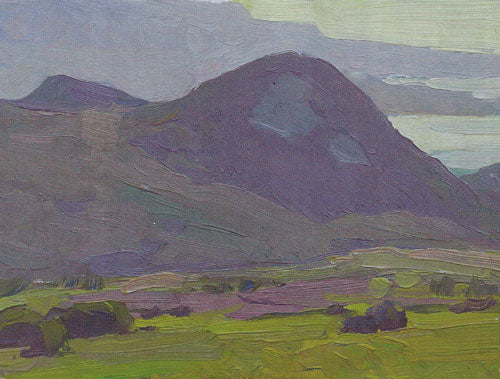

Glenn Dean, Hills Near the Bay, 2010, oil, 6"x8"

Collection of the artist; Plein air

Dean doesn’t go into the landscape with preconceived, solid ideas about what he will paint at a location. Rather, he expects to paint only “the little corners of the place,without expecting to do anything but capture the moment. After he returns from an extended painting trip, it takes him about six months before he is able to determine how he will use the sketches. “I try to just paint and let myself respond as honestly and as individually as I can,”says the artist. “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what or how to paint because I find that the best paintings come from an instantaneous response to what just happened. I look and immediately go for a direct response to what I see. I seldom use those field studies right away, preferring to wait until I can form a solid idea o f what to do with the sketches. Most times I don’t even leave the plein air paintings out in the studio where I can see them because I want to put them aside and then have them within my field of vision when I start to develop a big painting in the studio. Ideas for those studio works will form quickly as an immediate response to what catches my attention when I glance at the sketches.

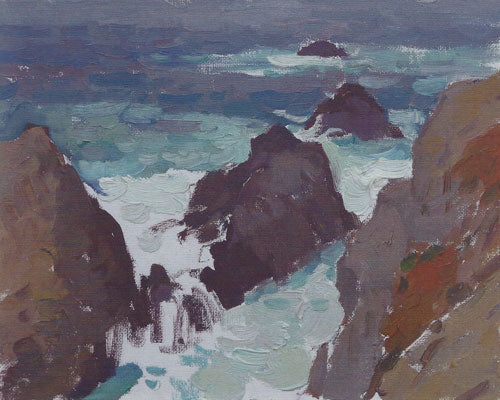

Glenn Dean, Crescendo, 2013, oil, 8"x10"

Courtesy Maxwell Alexander Gallery; Plein air

Once Dean has distanced himself from the moment recorded in a plein painting, he asks himself how he can use the study and a few reference photographs to paint the “big effect” on the landscape. He says, “When I am in the studio, I am still trying to achieve the effect of light and dark as well as a sense of design, and I try to solidify the ideas implicit in the location by attempting to gain from the bigger pool of what that experience was like. I want to use the energy in the plein air pieces while expanding the information.

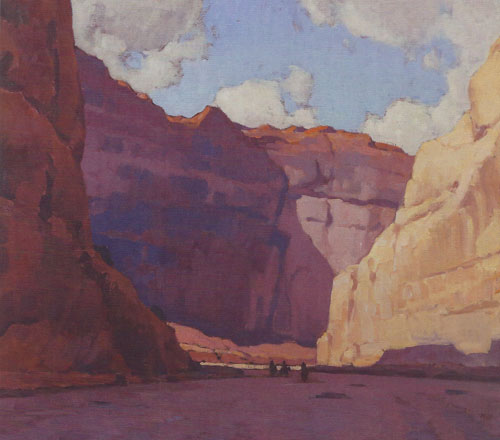

Glenn Dean, Canyon de Chelly, 2014, oil, 36"x40"

Courtesy Medicine Man Gallery; Studio

“I used to make a lot of changes as I developed studio paintings from my plein air sketches, but I found myself being disappointed that I lost the initial impetus in the editing process and put myself in the position of never knowing when the painting was finished. I decided to let the painting dictate what needed to be done without obliterating its identity. Now, most of the changes I make are relatively minor and are refinements of the composition rather than wholesale changes. I just need to know the painting has good drawing, good color, and good design.”

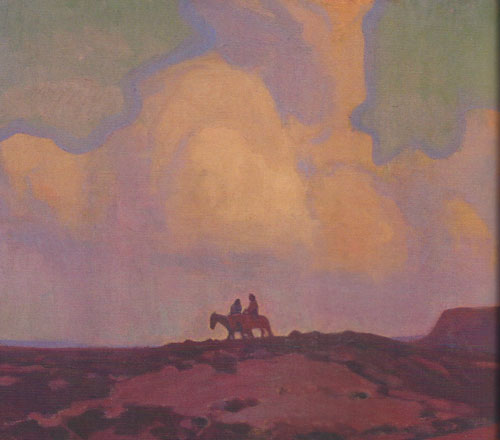

Glenn Dean, Receding Storm, 2013, oil, 20"x24"

Courtesy Thunderbird Foundation; Studio

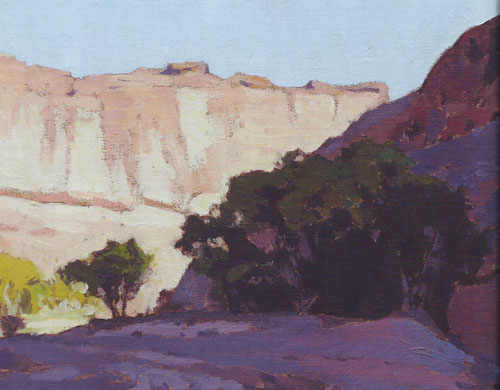

Glenn Dean, Canyon Shadow, 2014, oil, 9"x12"

Courtesy Maxwell Anderson Gallery; Studio

Asked to identify the most important elements of a painting from his perspective, Dean deflects the question, saying that any of a handful of attributes can make a painting successful. “At any given time, one of those can become more important - color, drawing. Or composition," he says. "One painting might be about the color relationships while another might have very little color variation but a strong design. It all depends on what I am trying to say with a painting, and that message has to honor the location. If I’m painting under bright sun in the middle of the day, then the painting has to say that. I might say it with high-key colors, for example, or contrasting value relationships.”

M. Stephen Doherty is editor-in-chief of PleinAir