Joseph Henry Sharp, Part 4

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Joseph Henry Sharp, Part 4

Teepee Smoke, Part 4

Reprinted courtesy Western Art Collector, January 2008

After travels through Europe to further master his craft, Joseph Henry Sharp again felt the pull toward New Mexico

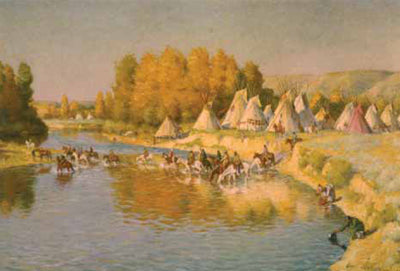

J. H. Sharp, Camp on the Little Big Horn, oil, 27 x 40”

PHOTO COURTESY COLLECTION NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, WASHINGTON, D.C.

By 1890 Sharp’s studio sales increased, and with the added earnings from his commission work, he and his wife Addie were able to save enough money to spend the coming summer months in Taos.

After staying in Santa Fe for a few weeks, Sharp and Addie rented a wagon and drove to Taos Pueblo. Of the 401 Indians residing in the pueblo in 1890, only five could read, write, and speak English, and of the 387 who spoke Spanish, only one could read and write it. Their primary language was Tiwa, a complex language which sounded to outsiders like a series of grunts and vocal lunges. Although lipreading Tiwa was impossible, even with his hearing impairment Sharp was somehow able to understand more in a conversation with the Indians than those who could hear but did not understand the language.

Sharp enjoyed painting Indian portraits, or “heads” as he called them, and did not limit himself to Taos Indians. In 1890, the total population of the nineteen pueblos in the New Mexico territory was 8,287; in addition, there were 5,169 Navajos and 1,321 Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches. Sharp traveled by buckboard to many of their reservations to paint and sketch before he and Addie returned to Cincinnati at summer’s end.

J. H. Sharp, Lament for the Dead, oil, 33 x 47”

PHOTO COURTESY GILCREASE MUSEUM, TULSA, OK

A new pattern was now becoming visible in Sharp’s work. He completed a painting that typified an attitude toward the Indians that would be found in many of his future works. Lament for the Dead shows an Indian mourning in the night, her arms uplifted in grief.

Sharp’s numerous burial scenes are not only portrayals of human suffering and grief, but are also metaphors for the death of the Indian way of life. Paintings such as Lament for the Dead always depict “the old ways,” and although in reality there might have been a telegraph pole or kerosene lamp or train in the background, Sharp never put it in the painting.

Since Sharp produced the etchings while in Cincinnati, where Indian models were not available, he usually referred to his collection of photographs, oils painted during his summers out West, or other etchings. His natural ability with this technique resulted in beautiful etchings remarkable for their composition and facial likenesses. But the plates were made only for the joy of the experience. He pulled a total of 23 etchings of Bull Thigh, but only a few each from the other plates.

J. H. Sharp, Soaring Eagle, oil, 20 x 10”

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE COLLECTION OF PATRICIA AND ROGER FRY, CINCINNATI, OH

Summer rolled around again, and it was back to the west for Sharp and Addie. They set up housekeeping in Taos in a convenient old adobe about three miles from the pueblo. Although it was only Sharp’s second summer in Taos and his third visit in six years, newspapers were already calling in an “annual trip.”

Back in his beloved Indian country, the land of manana, Sharp felt relaxed and buoyant once more, pleased to be away from the noise and dampness of Cincinnati. Now well known to the Indians, the artist found himself besieged by potential subjects; often he would awaken in the morning to discover a dozen or more Indians—men, women and children-waiting for him to begin work, each one anxious to be selected as the day’s model. They loved tobacco, and Sharp kept an ample supply of cigarettes and cigars. Frequently several would sit smoking in the studio while he painted one of their friends. Soon the room would be so clouded with smoke that he would have to pause in his work, shoo the Indians outside, and allow the room to air before continuing.

J. H. Sharp, Standing Deer, etching, 5 x 3” Sharp experimented with different media, making at least 21 etchings, one dry point and one aquatint. PHOTO COURTESY OF FORREST FENN

One day he was visited by about 30 braves dressed in tribal finery because they had just come from a dance at the pueblo. They gathered around him as he worked, grinning and nudging one another as they wandered curiously about the studio. When they had been entertained to their satisfaction, they suddenly rushed outside, mounted their waiting ponies, and thundered away, whooping and hollering in a swirl of dust while Sharp stood by, accepting their behavior patiently and without complaint.

Understanding the Indians was an important part of Sharp’s business. Although Alexis Compera, a Frenchman, had painted in Taos in 1879, Charles Craig had visited there in 1881, and Henry Poore, who wasn’t much of an artist, was there briefly in 1890, Sharp was the first artist to spend any length of time painting in Taos.

J. H. Sharp, American Horse—Cheyenne Chief, oil, 14 x 10”

PHOTO COURTESY COLLECTION OF THE PHOEBE APPERSON HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

American Horse, wearing an army officer’s coat, strikes a serious pose for Sharp’s camera.

PHOTO COURTESY OF FORREST FENN

Of all the models who posed for Sharp in Taos, his favorite was Soaring Eagle. Their first encounter occurred one morning when the Indian peered in the window of Sharp’s adobe house, then tried the door, and receiving no response, sat down to wait until someone was up and about. When Sharp finally opened the door, he found Soaring Eagle standing there with two eggs in his hands. He walked the three miles from the pueblo to offer the eggs as a gesture of friendship. Sharp accepted them warmly and thus began a close relationship that lasted for many years. Soaring Eagle was the first Southwestern Indian whose portrait Sharp painted. Although the Indian was usually reliable, there were times when the artist was disappointed because Soaring Eagle would fail to appear for a scheduled sitting. The Indian knew that the two dollars he received from the artist for each sitting was more than adequate pay; nevertheless, he often pleaded to leave early, to be paid more, or to borrow small sums of money for coffee and sugar, or for some allegedly sick relative.

Sharp usually capitulated, unwilling to strain an otherwise beautiful working relationship. And his patience was rewarded. One afternoon when Sharp was painting on the open plain about two miles west of the pueblo, Soaring Eagle came riding up on his pony and persuaded the artist—paint box and easel in hand—to mount up behind him. The Indian spurred his pony and they took off like a shot. Sharp hung on desperately, clutching his box and easel with one arm and his friend with the other. The Indian chuckled all the way, then as abruptly as he had started, drew the pony to a stop, causing Sharp to half tumble to the ground. The artist was furious until he looked ahead and saw a hundred or more braves preparing for a rabbit hunt. He realized that Soaring Eagle had wanted him to see the Indians in a natural setting, a scene much more interesting than any he could have imagined.

Sharp had hundreds of teepee photographs.

The summer of 1898 was especially productive for Sharp. For the last three years he had averaged two paintings a week and would continue to do so for the next forty years. Many of the “heads” he painted were duplicated later in monotypes, and his dance scenes and landscapes were developed further on larger canvases completed during the cold winter months in Cincinnati.

Sharp viewed the Indian as an equal, and his paintings lend dignity to everyday scenes such as the shelling of corn, of the handsome maidens Crucita and Leaf Down sitting on bancos in soulful repose. However, the half-clothed braves from Taos occasionally seem to be standing in stuff, awkward poses. In these paintings, Sharp seems to have been more preoccupied with the way the color and light glanced off his model’s red skin than with the personality or activity of the model. He once commented to a reporter that Pueblo Indians did not interest him as subjects until he “got them in the sun or by the firelight.”

About Forrest Fenn:

Forrest Fenn grew up in the wilds of Montana where he began finding arrowheads and other small Indian artifacts. His hobby developed into a career of collecting, buying, selling and trading not only artifacts but also weapons, weavings and pots. The collection grew, the reputation grew, and the hobby grew into a business. Forrest finally opened a trading post that expanded to include sculpture and paintings. The collector became a dealer and he built a large, beautiful gallery which included works by Joseph Henry Sharp. The images reproduced here are from the book Teepee Smoke A New Look Into the Life and Work of Joseph Henry Sharp originally published in 1983 by One Horse Land & Cattle Co. with kind permission Forrest Fenn. Copies of this book can be purchased online at www.oldsantafetradingco.com