View Josh Elliott's available paintings

Josh Elliott: Tapestries in Oil

By Bob Bahr

Reprinted courtesy of American Artist Magazine, December 17, 2006

Josh Elliott, Passing Clouds, Radersburg, Oil on Panel, 18" x 54"

Josh Elliott is 33 years old, but in the best tradition of good artists—or anyone whose job requires continual growth—he remains an avid student of his craft. Many of his plein air outings involve experiments with design, color, or invention. Elliott already has enormous facility—one friend of his, an established artist who sells paintings for tens of thousands of dollars, saw a recent Elliott piece and jokingly muttered, “Somebody needs to break his hands.” Elliott is done with simply capturing picturesque scenes—“I’m not driven by subject matter anymore,” the painter states. Now he hopes his pieces have the allure of a rug. Yes, a rug.

“All the colors come together so well in a beautiful Persian rug,” says Elliott. “I want to paint a painting that’s like one of those rugs, or like a tapestry. I’ve been more carefully designing my compositions for colors and values, going not for a focal point but rather for an overall feeling. These paintings are very thought out and planned.” He’s using his brain as much as, or more than, many painters, but one senses that Elliott is suspicious of the highbrow. “I don’t see art as an elevated thing,” he says. “It should not exclude. When people around here say they feel they don’t understand a piece, really what they’re saying is they don’t like it. I respect that—you like what you like.” He considers his process a “blue-collar approach,” and although the oil painter’s depictions of the mountain meadows, river canyons, and working farms of his native Montana are decidedly no-nonsense, they are also thoughtful and pretty. Like a tapestry or an artful rug.

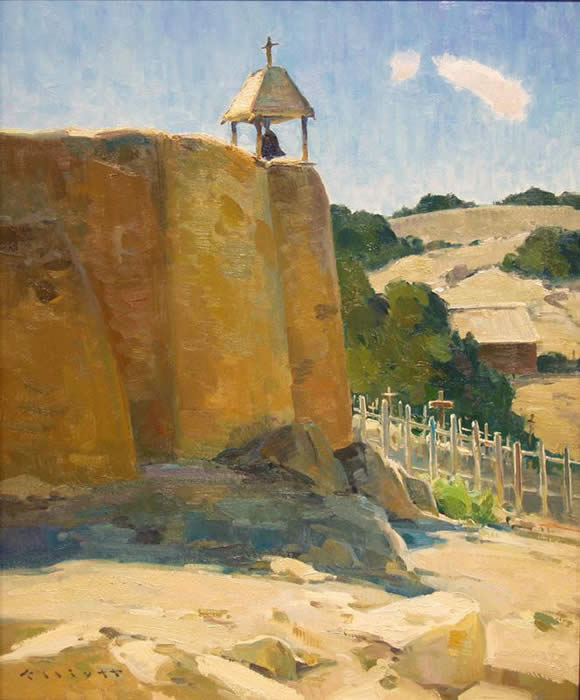

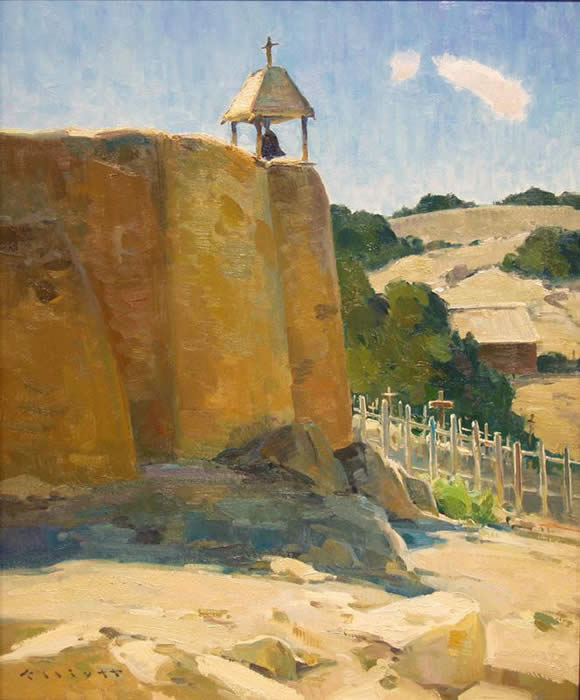

Josh Elliott, Las Golondrinas Church, Oil on Panel, 24" x 20"

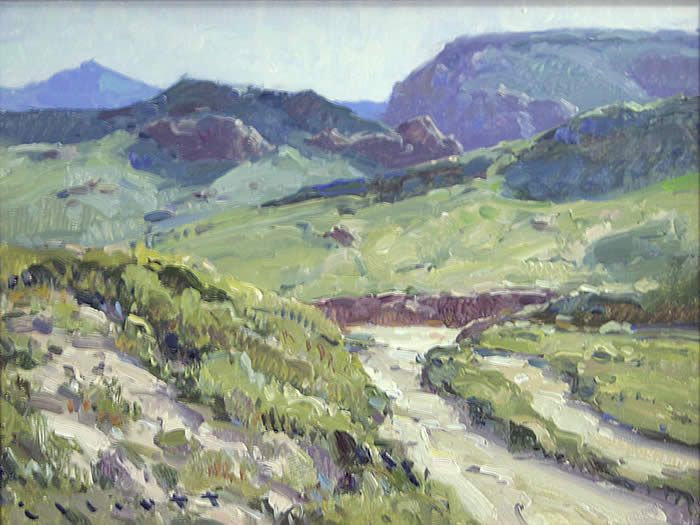

Lately, Elliott has been concentrating on tone. His earlier work contained some high-contrast passages, but the artist is currently enjoying creating works with a limited value range and a harmony in temperature and color group. For instance, one painting he executed last spring featured rusty brown hills and yellow light. The trees were spring-green, but Elliott painted them golden so they harmonized with the earth tones on the canvas. (He did use cool blues in the trees’ shadows.) “Sometimes it’s a study of how brown I can make a scene—or how blue—and still make it read,” says the artist. “I think of some of these new paintings as tone poems.” Such paintings are inherently moody, and Elliott likes that—even as he carefully avoids dictating a specific mood. “Yesterday I painted the last light of the day—the trees looked pink, and the mountain’s shadow was coming over them. It created a feeling of nostalgia...or impending doom...or still, quiet, peacefulness. It depends on the viewer’s feelings about the scene, not just mine.”

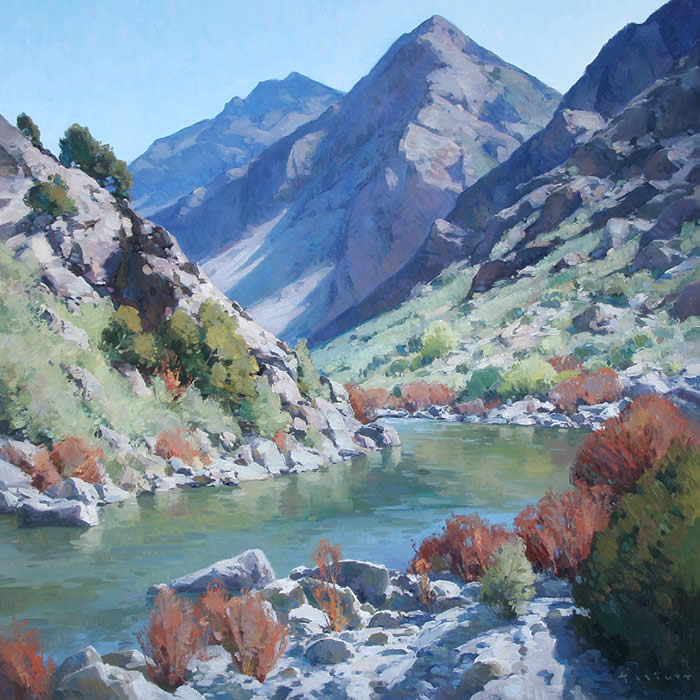

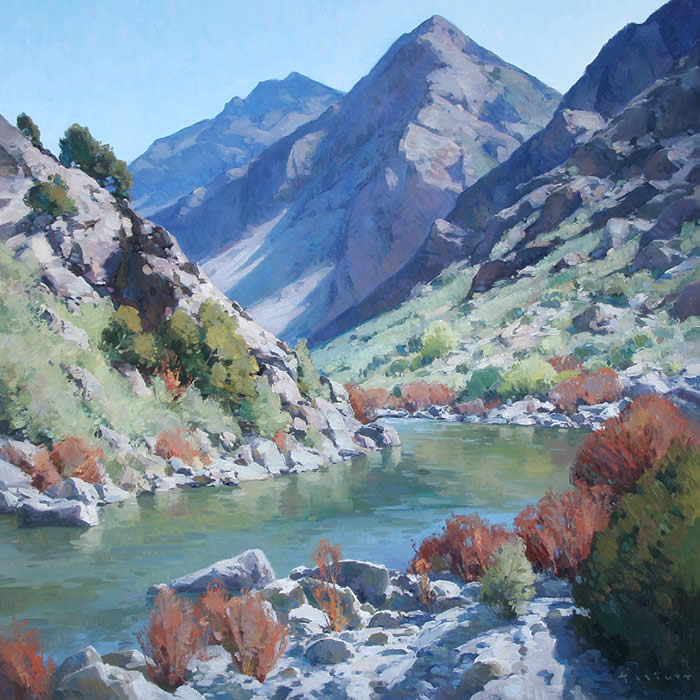

Josh Elliott, Rio Grande Spring, Oil on Board, 36" x 36"

This exploration is indicative of Elliott’s willingness to pursue change—be it in subject matter, composition, or the colors on his palette. His paintings of landscapes suggest great veracity, but the artist has no problem rearranging elements to create stronger compositions. He cites the work of Victor Higgins, Rockwell Kent, and the Group of Seven—the Canadian landscape painters Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley—as inspirational in this regard. “They were all artists who really owned their images,” says Elliott. “They were not slaves to nature. It takes some courage to move things around, and it also takes awhile to know how to make it work.” Thus, trees can be moved and turned orange in his paintings if the artist thinks it will improve a piece.

For years, Elliott worked with a basic palette consisting of titanium white, French ultramarine blue, cobalt blue, cadmium red, cadmium yellow light, virdian, and one surprising hue—cobalt violet. “My dad painter, Steve Elliott, had some on his palette, and I started using it instead of cadmium red,” he says. “Cobalt violet is a little subtler; it warms things up, but not too much.” He recently expanded his palette significantly, adding quinacridone rose, Indian red, cadmium orange, permanent green, turquoise, chromium oxide, raw umber, and yellow ochre because he wanted richer colors. “At first it looked like somebody dumped a bag of Skittles on my canvas,” says Elliott, “then I reined it in and really started having fun.”

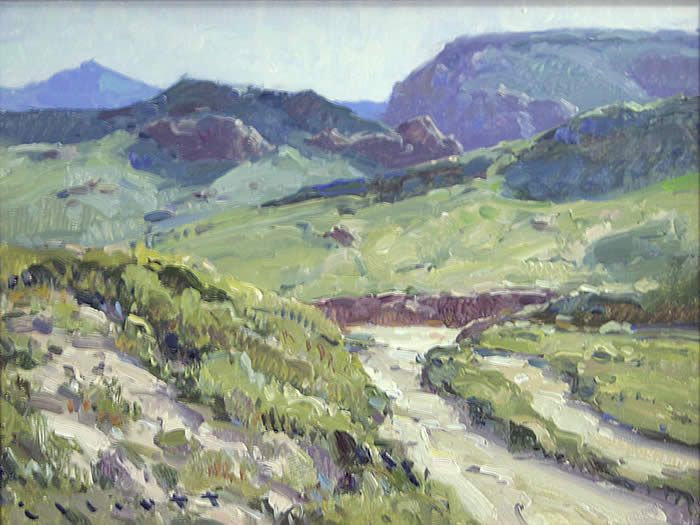

Josh Elliott, Desert Wash, Oil on Panel, 9 " x 12 "

He’s not loyal to any particular brand of paint or brush, but he favors big brushes in general—sizes 6 through 12—and uses a coarse hog’s-bristle brush for his first thin wash, which he lays in as a road map for the painting. After sketching the composition in, using thinned oil paint as if it were watercolor, he switches to a smoother synthetic brush for thicker paint application. “Sometimes I let the wash show through, and sometimes I cover it all up with opaque paint,” explains Elliott. He may start with middle values, but the artist estimates that 70 percent of the time he begins by laying in his darkest darks. He then moves on to the middle values and, finally, the highlights. The artist likes to start with the area of the composition that excites him the most, and he finishes each section as he goes. “I usually block in with intense colors—I can always mute them,” he says. “I try to maintain big shapes from the beginning because those are what will allow the painting to read from 50 feet away. Because I finish as I go, I try to keep my brushstrokes as suggestive as possible all the way through.” This approach is readily apparent in Elliott’s depictions of scree fields, logs, and, especially, water.

Josh Elliott, Montana Spring, Oil on Panel, 24" x 30"

A few years ago, Elliott was perhaps on the verge of becoming known as a masterful painter of water, particularly streams flowing over multicolored rocks. So he stopped painting it. “I didn’t want to get stuck in a subject matter,” he explains. “It just didn’t excite me anymore; I felt like it was time for me to move on. I still paint it, but only when it makes sense. There are artists who focus on series, but that’s just not me.” Water still turns up in a lot of his paintings because it’s often a crucial compositional element. But the lasting effect of Elliott’s stint painting rocks underwater is most easily seen in his ability to capture a scene’s rhythm and harmonic colors, unified by a reflected sky and suggested with fresh, dappled brushstrokes. “Maybe that’s where my idea of a painting looking like a tapestry came from,” he muses. As the number of streambeds in his paintings dwindles, man-made structures—particularly farmhouses and their outbuildings—show up more frequently. Elliott considers them interesting design elements, but they also allow him to celebrate farmers and cattlemen through his work. “These people are hard workers,” he emphasizes. “They don’t get enough recognition. In our state, at least, they are the grease that allows the wheel to turn. I don’t work as hard as they do, but I relate to these guys. Plus, it’s interesting to think about how people get by on this planet. These buildings help tell the story.” He’s also open to a wildcard—letting someone else pick the subject matter. “Sometimes when I’m with one of my painting buddies, someone will pick a spot where I don’t initially see anything I’m interested in,” he says. “But I stay there, and I find something. I’m not really afraid to paint anything right now. I used to be afraid of failure, but sometimes painting something that you think might result in a failed painting can turn out really well. You learn a lot, and the result can be great. Someday I want to make a McDonald’s beautiful—I just have to paint it in the right light.”

Josh Elliott, Spring, Oil on Panel, 10" x 12"

Appropriately, Elliott not only references Edgar Payne’s classic treatise Composition of Outdoor Painting (De Ru’s Fine Arts, Bellflower, California) but he also quotes the passage that in a sense advocates throwing out all the rules but still creating a successful painting. “I like organizing the rocks in a scene into a pattern, one that allows me to move the viewer’s eye around in the painting,” he says. “If you make the pattern as random as the rocks really are distributed in the landscape, it’s going to be a random painting. Payne talks about purely random paintings—I think that would be interesting to try.”