Snapshots of the Past

By Medicine Man Gallery on

Snapshots of the Past

Early images of Native Americans document historical period of cultural discovery

by John O'Hern

Published online courtesy of Western Art Collector, February 2014

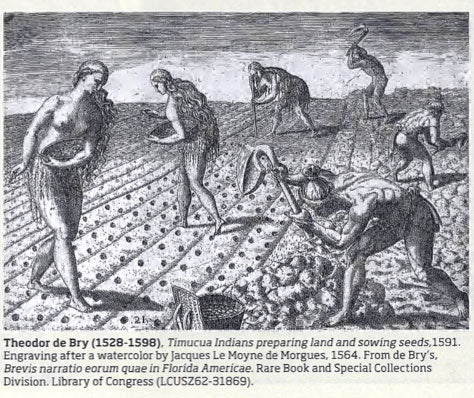

Some of the earliest images of the inhabitants of the New World were drawn by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues (1533-1588), a French Huguenot artist who accompanied Jean Ribault's and Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere's attempt to colonize northern Florida in 1564. Le Moyne recorded the flora, fauna and people of the region in a series of drawings and watercolors, most of which were lost in a Spanish attack on Laudonniere's Fort Caroline the following year.

When Le Moyne returned to Europe he recreated the images from memory. They were reproduced as etchings by the Belgian printer and publisher Theodor de Bry (1528-1598). Scholars debate the accuracy of the details in the images both because they were initially recreated from memory and then translated to another medium by a different artist. In the engraving, Timucua Indians preparing land and sowing seeds (1591), the inaccuracies are obvious. The men and women are incongruously Greco-Roman, and the women are using European tools.

Charles Bird King (1785-1862) fared better in his portraits of distinguished native leaders. Born in Newport, Rhode Island, he studied with Benjamin West at the Royal Academy in London. He settled in Washington, D.C., and became the favorite portrait painter among the political elite. He was commissioned by the then Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) to paint portraits of Native American leaders who were brought to Washington to meet President James Monroe at the White House in 1821. He painted Indian portraits for the OIA for the next 20 years. Nearly all of his paintings were destroyed in a fire at the Smithsonian Institution in 1865.

Charles Byrd King (1785-1862), Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight), ca. 1822, oi on panel, 17.5"x13.9". The White House Historical Association.

Fortunately, King had painted copies. One of those copies, now in the collection of the White House, is of Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight), a member of the Oto Tribe. Monroe had offered to send missionaries West to teach the people about Christianity and agriculture. Sharitarish, or "W cked Chief" of the Pawnee Tribe, who was also painted by King, told the president they preferred their traditional ways and "We have everything we want - we have plenty of land, if you will keep your people off it." The attempts by the federal government to gain Native American support for Western expansion failed. In another omen of the future of the native peoples, Hayne Hudjihini contracted measles and died shortly after returning to her home.

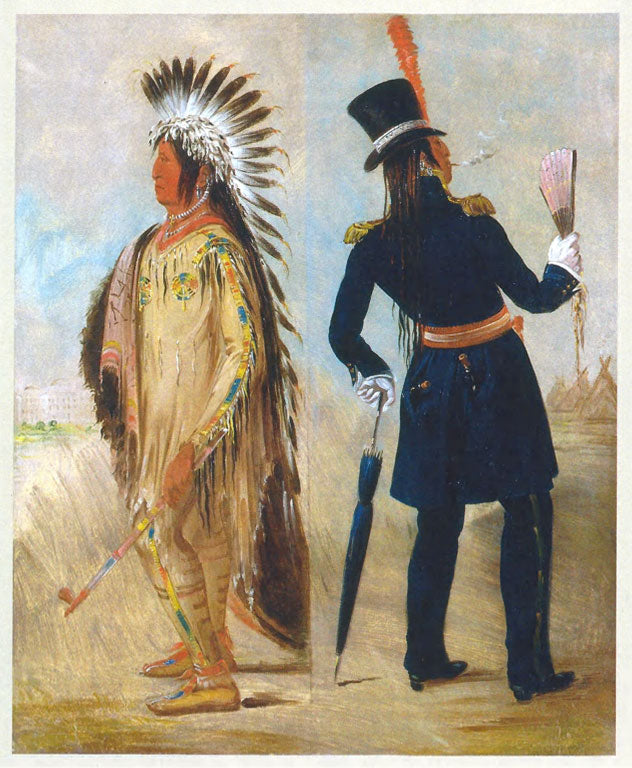

George Catlin (1796-1872), Wi-jjn-jon, Pigeon's Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington, 1837-1839, oil on canvas, 29"x24". Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Native American visitors to Washington were often dressed up in Anglo Sunday-go-to-meeting finery by local merchants. George Catlin (1796-1872) satirized the practice in his painting Wi-jun-jon, Pigeon's Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington (1837-1839). In his book The World of the American West, Gordon Morris Bakken quotes Catlin who wrote that Wi-jun-jon, an Assiniboine warrior, abandoned his traditional garb for a suit of "broadcloth, of finest blue, trimmed with lace of gold; on his shoulders were mounted two immense epaulets; his neck was strangled with a shining black stock and his feet were pinioned in a pair of waterproof boots, with high heels which made him 'step like a yoked hog.'"

After Wi-jun-jon returned to the Plains he was full of himself and tales of the white man's cities. His fellow tribesmen eventually tired of his tales, thought they were lies, and murdered him. In his book, Last Rambles Amongst the Indians of the Rocky Mountains and the Andes (1868), Catlin wrote that after seeing the Indian ambassadors arriving in Washington, "...nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting their country, and becoming their historian..."

George Catlin (1796-1872), Stu-mick-o-sucks, Buffalo Bul's Back Fat, Head Chief, Blood Tribe, 1832, oil on canvas, 29"x24". Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.

Catlin had painted his subjects in his Washington studio, and traveled West in the 1830s to paint the Plains Indians, their life and their customs. He assembled his paintings and his collection of artifacts in an Indian Gallery. After Congress refused his proposal that they buy the paintings, he took them on a tour of European capitals in 1839. In 1852 he was forced to sell the gallery, which had grown to more than 600 paintings. The new owner, Joseph Harrison Jr., stored the paintings in his steam boiler factory in Philadelphia. Several years after his death, his widow donated them to the Smithsonian.

Karl Bodmer (1809-1893), Mato-Tope, A Mandan Chief, 1840-1843, hand-colored aquatint engraving, 51.82 cm x 36.07 cm. From Maximlian, Prince of Wied's Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832-1834. Library of Congress.

The Swiss-born artist Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) accompanied his German patron, Prince Maximilian of Wied (1782-1867) on an expedition to the Upper Missouri River. Maximilian's journal,Travels In the Interior of North America in the Years 1832 to 1834, was published following their return and contained 81 aquatint plates Bodmer had made of his watercolors from the expedition. Bodmer's portfolio of the campaign contained more than 400 images. At the time of the expedition, Maximilian wrote that Bodmer "is a lively, very good man and companion, seems well educated, and is very pleasant and very suitable for me; I am glad I picked him. He makes no demands, and in diligence he is never lacking." Bodmer's watercolors are considered among the most accurate and appealing early images of the period.

The translation from watercolor to aquatints by other artists and the dissimilarity of the two media led to some changes in detail, however.

John Coleman CA, Mato-Tope, Four Bears, bronze, ed. of 35, 36-1/2' tall. Bodmer-Catlin Series. Courtesy Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

The contemporary sculptor John Coleman has produced his Explorer Artists Bodmer-Catlin Series based on the paintings of the two 19th-century painters. "It is not my intention to add or take away from these works," he explains, "but to use these portraits and extensive historic research to capture sculpturally, the essence of who these men really were; to interpret in my sculptural style a three-dimensional portrait that will be a respectful complement to the original paintings."

John O'Hern, who has retired after 30 years in the museum business, specifically as the Executive Director and Curator o f the Arnot Art Museum, Elmira, N.Y., is the originator o f the internationally acclaimed Re-presenting Representation exhibitions which promote realism in its many guises. John was chair of the Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts. He writes for gallery publications around the world, including regular monthly features on Art Market Insights and on Sculpture in Western Art Collector magazine.