Maynard Dixon's "forgotten men" on view at BYU Museum of Art

By Medicine Man Gallery on

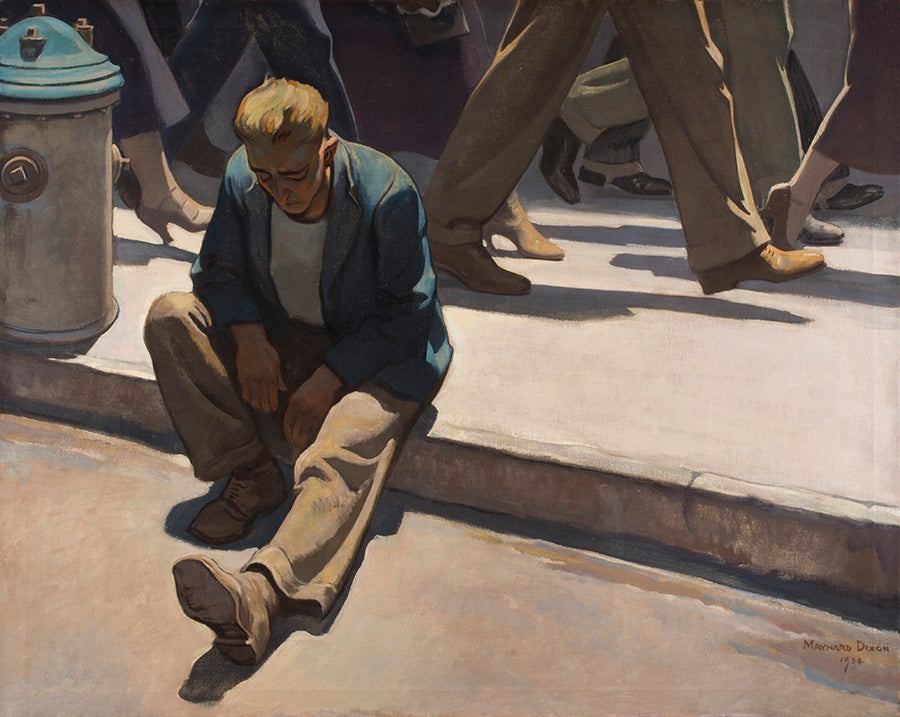

Maynard Dixon, Forgotten Man (1934) | Courtesy BYU Museum of Art

Hard times. Maynard Dixon knew them.

During the Great Depression, he and his wife Dorothea Lange shared the experiences of millions of Americans. Hunger. On the verge of homeless.

Out of this trauma came an exceptional and little-known body of work from the artist dedicated to what he called “the forgotten men,” casualties of the Depression like himself. Dixon’s “forgotten men” are among 70 artworks on view at the BYU Museum of Art for the exhibition “Maynard Dixon: Searching for a Home” through September 23, 2023.

“When the stock market goes down, that means new commissions for murals and portraiture goes down and so he and Dorothea Lange were in really serious economic straits a few times during the Depression where he really didn't know how they were going to make it through,” exhibition curator Kenneth Hartvigsen said.

Dixon was nearly 55-years-old when the stock market crashed in 1929 precipitating the Great Depression. He’d worked hard to build his career as a painter and muralist. He’d established himself. Lange, too, who ran a portrait studio where they lived in San Francisco.

Throughout the 1930s when times were hardest, he was of an age where in a later era retirement would have been just around the corner.

Hardship is never easy, but it certainly isn’t an old person’s game.

“What we see is not only that he was being really challenged by and stirred by the things he was seeing firsthand – people struggling in the Great Depression, documenting dockworkers strikes and things that he would have seen in California – but I think then those social realist paintings also become kind of a self-portrait for Dixon,” Hartvigsen said.

Dixon rarely produced traditional self-portraits throughout his career. Reading these “forgotten men” paintings in that context makes them all the more remarkable.

“We do think of him as a landscape painter and his landscape paintings are thrilling, but he's also a wonderful painter of people,” Hartvigsen said. “When he engages with the Western landscape, he's also engaging with the people who lived here – and that's across the board.”

Perhaps even himself.

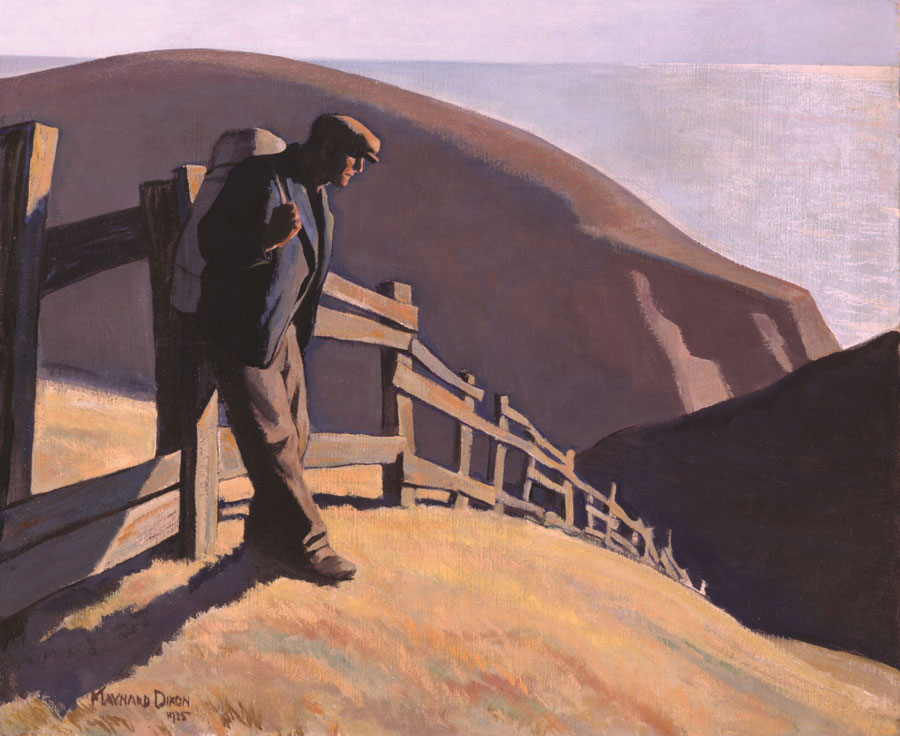

Maynard Dixon, No Place to Go (1936) | Courtesy BYU Museum of Art

Making matters worse, Dixon and Lange would divorce in 1935. Lange’s influence on Dixon’s artistic output during the runup to their split is fascinating to think about.

Any consideration of his paintings related to the Depression require mention of her photographs of the same subject during the same period. Lange’s candid, sensitive portrayals of migrant camp workers and the downtrodden resulted in her becoming one of the most important photographers of the 20th century. Her “Migrant Mother” (1836) picture is as famed an image as has ever been captured.

“I think we see a clear connection between the types of photographs (Lange) was taking and the types of things he was painting,” Hartvigsen said.

“Searching for Home” features the resplendent landscapes Dixon is best loved for. Visitors will enjoy the mesas, the mountains, the vast expanses of the Southwest he so cherished. There’s portraiture here, too. Native Americans. Farm workers. Folks. But it’s his brooding, restless, “forgotten men,” strong in stature, robbed of their work, their way of earning a living, of providing for their families – their manhood – and Dixon’s internalization of what they were going through where the exhibition reaches its apex.